What is the relationship of the Old Covenant to the New Covenant in the Bible?

Before that can be answered, one must first understand what the word “covenant” means. In general, theologians with no background in law attempt to answer the question without knowing what a covenant is.

A covenant is a contract (formal agreement) that is binding, not only on the original parties, but on their successors and assigns. Covenants pass from parents to children, from sellers of real property to purchasers, and so on. Marriage is a covenant.

All covenants are characterized by essential components. They are:

1. There are two or more parties.

2. All original parties enter the agreement voluntarily.

3. All original parties must be of sound mind.

4. All original parties must be of the age of majority (not minors).

5. There are witnesses to the declaration of the original agreement.

6. There are specific terms (conditions) to the agreement.

7. The terms are enforceable.

8. There are real and enforceable penalties for violating the covenant.

So a covenant is a subset of a contract.

In modern application, a contract is signed by the parties and binding only on the parties or the corporate entities they represent. Their signing is not witnessed. In modern covenants, the parties’ signing must be witnessed by an official third-party–in our country, typically a notary.

In addition to the essential components enumerated above:

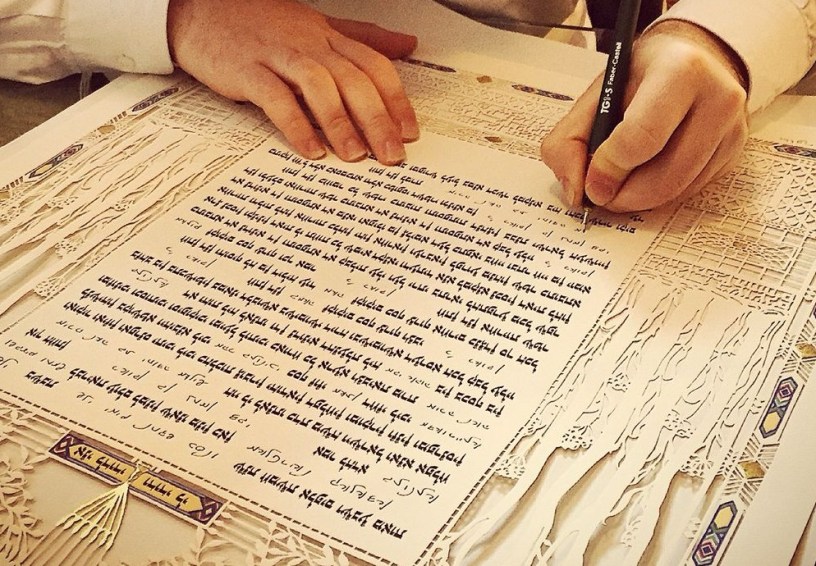

9. Most covenants are written.

10. The original document or an official copy thereof is housed in safe location, administered by a duly-appointed institution employing official, professional custodians, charged with its preservation.

11. The document and/or its official copy are available for public viewing.

If one does not understand these basic components of covenants in general, one is sure to stray far when trying to understand what the Old and New Covenants of the Bible are, how they are akin, and how they differ.

The basic nature of the New Covenant is introduced in Jeremiah 31:31-36

Look, the days come, says YHVH, that I will cut a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah–not according to the covenant that I cut with their fathers in the day I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt (which covenant of mine they broke, although I was a husband to them, says YHVH).

But this shall be the covenant that I will cut with the house of Israel: After those days, declares YHVH, I will put my Law (Torah) in their inward parts, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their Elohim, and they shall be my people. And they shall no longer each man teach his neighbor, and each man his brother, saying, “Know YHVH,” for they shall all know me, from the least of them even to the greatest of them, declares YHVH. For I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sins no more. So says YHVH, who gives the sun for a light by day, the laws of the moon, and the stars for a light by night, who stirs up the sea so that its waves roar, YHVH of Hosts is His name, if these ordinances depart from before Me, says YHVH, the seed of Israel also shall cease from being a nation before Me forever.

Who are the parties to this New Covenant? YHVH, the house of Israel and the house of Judah. If one wants to be party to this covenant, one has to be or become part of one of these two houses. Paul discusses the significance of the gentile being grafted into Israel in his letter to the Romans.

What are the terms of this New Covenant? The Torah. As verse 36 states, its ordinances shall not pass.

What makes this covenant new? As with the Old Covenant, it is written, not merely on vellum or stone, but on the heart. However, the New Covenant is written on receptive rather than stony hearts. It also provides a mechanism of forgiveness not available with the Old Covenant. Jeremiah only broaches these features without elaborating on them. One has to search the scriptures to draw out the details.

There is no indication in Jeremiah that a different Torah is involved. To the contrary, its ordinances are explicitly affirmed.

The author of Hebrews states that the New Covenant is founded “on better promises.” Ancient Israel was not promised eternal life in exchange for following the Old Covenant. It was promised temporal blessings such as good health and personal and national prosperity. The New Covenant offers forgiveness for capital sins and eternal life.

Some covenants are layered on other covenants, running parallel with them while the earlier ones remain fully in force. The covenant of Sinai was layered on the covenant of circumcision, which was layered on the Noachide covenant.

The New Covenant supersedes some aspects of the Old, its superior promises being one such aspect. However, the standards of behavior are identical, as are various other features.

Much more could be said regarding the covenants, but I consider the above the most basic foundation upon which personal study can build.

It is critical to note that “Old Covenant” and “Old Testament” are not synonymous with one another. Neither are “New Covenant” and “New Testament” synonymous. The assumption that they are has led to no end of confusion. A testament is a declaration–a formal statement. A testament such as a will can be binding on heirs, so a “testamentary will” or “last will and testament” is a type of covenant, but that does not make all testaments covenants.

If you get the sense that some of this is outside the scope of theology and more the arena of the attorney, you are right. I became aware of these things, not in theology school, but in my professional life working with land use law.

We refer to what Christians call the “Old Testament” as the “Tanakh.” This (תנך) is a Hebrew acronym for Torah (Law), Nevi’im (Prophets) and Ketuvim (Writings), its primary subdivisions. We do not wish to assign it a name that implies it is outdated, outmoded, discarded or superseded.

As to what we observe and what we do not, I think the following will clarify that:

Yehoshua said, “Do not think that I came to annul the Law (Torah) or the Prophets; I did not come to annul, but to fulfill. Truly I say to you, until the heaven and the earth pass away, in no way shall one iota or one point pass away from the Torah until all comes to pass. Therefore, whoever relaxes one of these commandments, the least, and shall teach men so, he shall be called least in the kingdom of heaven. But whoever does and teaches them, this one shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

There is little room for mistaking his words here, even in English translated from the Greek, but if one wants to debate, in his own language he said that not one “n’quddah” (point, dot, speck) and not one “ot” (letter, mark) will pass from the Torah until heaven and earth are no longer.

The words “Law” or “Torah” can be used to refer specifically to the first five books of the Bible or to just the instructional material in those books. It can also refer to the entire Tanakh. It can also refer to oral instructions. Many people are critical of oral instructions, but the calendar by which we identify the biblical holidays is a great example of something we do that is dependent on oral instructions since the Bible is not explicit as to how the calendar works. So “Law” or “Torah” can mean different things. A problem arises, however, when people deploy different uses of these terms to circumvent God’s instructions.

How did Yehoshua use the term? One interesting example is in John 10:34:

Yehoshua answered them, “Has it not been written in your Law, ‘I said, you are gods?’” Interestingly, he is quoting Psalm 82:6.

Torah, the primary Hebrew word translated as “law” means “instruction.” There are several other Hebrew words translated as law, statute, ordinance, etc. Eight of them are repeated throughout Psalm 119. In any case, when Elohim gives an instruction, it is, by virtue of his supreme authority, law.

Christianity tends to divide laws into the two categories “moral” and “ceremonial.” This makes it easy to discard ceremonial instructions. However, the lists of instructions in Exodus through Deuteronomy often intermix the two, making it clear they are not to be dissected. Moreover, Christians are perfectly comfortable with ceremonies such as baptism, anointing, laying on hands and rituals relating to the “Last Supper.” So the mere distinction between moral and ceremonial doesn’t at all tell us what is applicable to us and what is not. Besides, if God tells us to do something ceremonial and we refuse, our rebellion becomes a moral issue.

In my next post, we’ll consider the different, basic categories of instructions in the Torah to better understand their contemporary and practical application.